It’s not often we get invited to a beheading event, so when friends of ours asked us if we wanted to observe the process of butchering chickens, we jumped at the chance. Wouldn’t you? Years ago, Kris and I had been interested in growing our own chickens, but we were growing so many children, it seemed a little overwhelming (to me) to add livestock into the mix. However, there was a lingering appeal to raising chickens the Joel Salatin way (https://youtu.be/TfT49gaiktg) and we recently found out that we had friends who were living the Salatin dream, albeit on a small scale. We’re both city slickers, so this was a great opportunity to find out how it’s done.

Don’t read any more of this if you don’t want to know all the gory details, which involves both blood AND guts. I’m giving you fair warning: if you’re the squeamish type, find the nearest exit. The rest of you can follow me around for the tour.

On the Day of Execution, we showed up at the appointed time wearing clothes that we wouldn’t mind getting blood spattered if it came to that. I only had one notion tucked into my brain about killing chickens and it involved a chopping block and chickens running around with their heads cut off. Silly me. Actually, I had two notions, the other one being that I didn’t intend being the one to deliver the short, sharp shock (a little Gilbert and Sullivan reference for those of you in the know).

The chickens were clucking contentedly in their little chicken tractor when we arrived. One of them was a rogue male who had accidentally been part of their chick shipment. He was a beauty, but scrawny and not destined for the dinner table.

We found out that it takes about 8 weeks to go from chick to chopping block. In that time, they had all become fat little buffers living on chicken feed, grass, water, sunshine and good animal husbandry practices.

When the scalding water got up to temperature, the moment of truth had arrived. One of these plump little hens was chosen, placed upside down in the chicken hopper, its head firmly grasped and the throat deftly cut. The whole process was very quick and humane. It took a couple minutes to allow the blood to drain out into a bucket and for the chicken to settle (the post-death convulsions are a real thing).

On to the scalding pot! Chickens come with these great little handles with which to hold them upside down. The scalding process is to loosen the feathers.

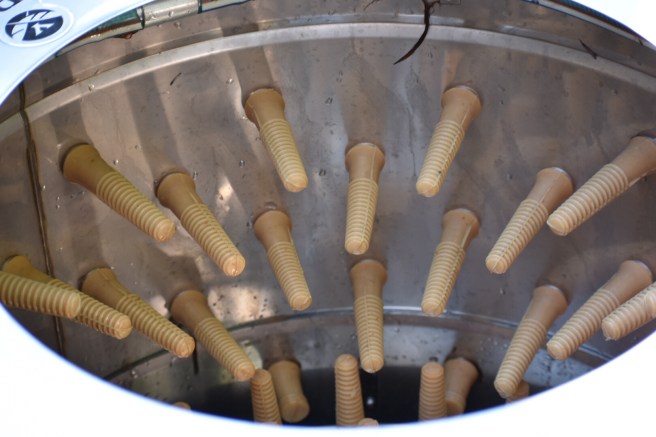

Once a wing feather can be easily plucked off without resistance (this usually takes less than a minute in the hot water), the bird can go into the de-feathering thingy, which is the slickest piece of machinery you can imagine. It’s filled with little rubber “fingers” that essentially pluck the feathers off while the chicken is bounced around and in 20-30 seconds, you have a naked bird, ready for gutting. Take a moment to appreciate the sheer genius of this labor-saving device. You can bet our friends appreciated it.

Okay, how much of this do you want to see? In for a penny, in for a pound, right? Those handles that came in so handy had served their purpose and were the first things to go. I’ve seen jars of chicken feet at the grocery store, so I know that it must be a delicacy for some people, but when we were offered some, I declined. They probably would have been good for making broth, but I don’t think I’m ready for the sight of chicken feet floating around in my pan. City slicker.

The head and tailbone are cut off and then you’ve gotta be willing to get your hands dirty and pull the guts and lungs out. The whole process took about 10 minutes from hopper to cooler. If you’re a meat eater (and I definitely am), it’s actually a good idea to know from whence it comes and how it got to your table.

Before we left, Kris took a turn at being Lord High Executioner (more Gilbert and Sullivan), so if we decide to do the thing, that’s been added to his skill set. And I’ve established that I can stand around taking photos, so we’re all set!

All in all, it was a good educational experience and my hat’s off to our friends who have decided to strengthen their connection between the farm and the table and to exercise good stewardship in the process. And not only that, they’re giving us a chicken for our table – that’s an exceedingly good gift!

I’ll probably delete this in the morning.